Tale of the day:

Working with Troubled Teens

Not many people realize that before I started my private coaching practice in NLP, I worked for two years as a counselor and trip leader for at-risk and troubled youth at a wilderness therapy program in Colorado. During those two years working round-the-clock shifts for three weeks straight, I learned more about human behavior than at any other time in my life. With each new three-week expedition, I never knew what new adventure awaited.

There was the time Toby drank his own pee and pooped in his hands, chasing the other kids around camp with his weapon of mass disruption, then dropping bio-terrorism in favor of threatening to stab me with his tent stakes…. There was the time Christine and Kendra cheeked their meds, crushed them up, and did lines off the toilet seat…. On our drive to New Mexico, Adrian had a temper tantrum and shattered the front windshield of the car…. And there was the expedition when Tom and Ken stole my car key and managed to use it to start the pick-up truck in the middle of the night, escaping to a nearby town where they robbed a ski shop before driving the wrong way down a one-way street only to discover a police car coming the other direction….

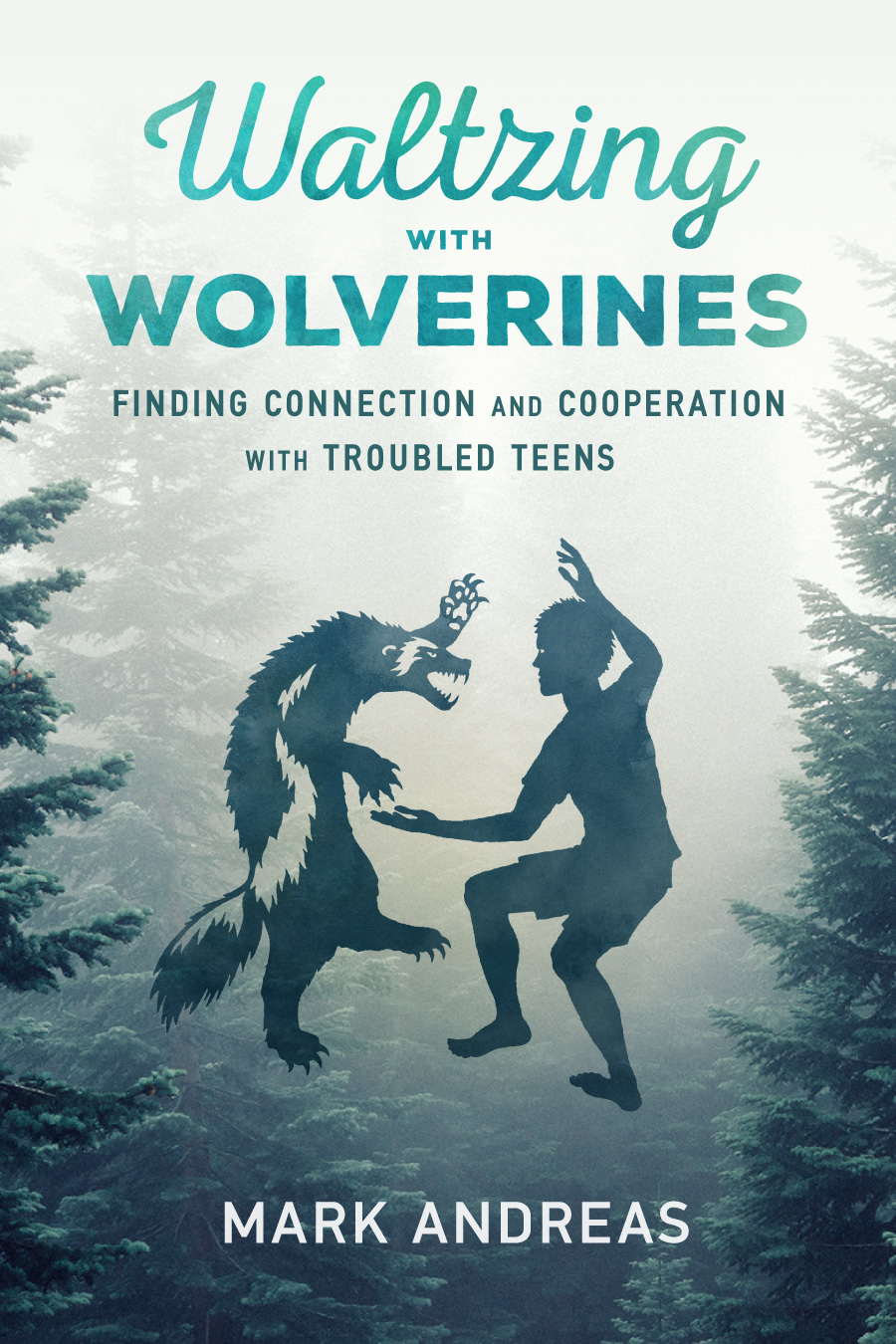

These experiences profoundly transformed my understanding of how to work with youth, teaching me vital lessons that I want to share with you, so you can be as impactful as possible with the teens in your life. That’s why I’m pleased to announce the release of my latest e-book, Waltzing with Wolverines: finding connection and cooperation with troubled teens:

The book is filled from cover to cover with tools and tales of change—both the stories from my direct experience, and the 48 principles that allowed me not just to survive, but to thrive while working in this non-stop chaotic environment. Most of us have teens in our lives – even if it’s just “the teen within.” So whether you want to just enjoy the stories, or want practical tools to use as a parent, teacher or youth leader, I hope you check out the introduction “The Key to it All,” below.

The book is filled from cover to cover with tools and tales of change—both the stories from my direct experience, and the 48 principles that allowed me not just to survive, but to thrive while working in this non-stop chaotic environment. Most of us have teens in our lives – even if it’s just “the teen within.” So whether you want to just enjoy the stories, or want practical tools to use as a parent, teacher or youth leader, I hope you check out the introduction “The Key to it All,” below.

If you read the book, please let me know what you think was useful, anything confusing, what was funny, etc. Here are a few pre-publication endorsements. All of my readers have given it a strong thumbs up so far!

If you already know you want the book, you can buy “Waltzing with Wolverines” here.

What people are saying about “Waltzing with Wolverines”

In “Waltzing with Wolverines,” Andreas redefines how to build relationship and trust with so-called “troubled” youth. In these pages, you’ll find a treasure trove of teaching and leadership stories, tools, and techniques. But this book is about much more than a list of behavior management strategies— it’s a clarion call to re-envision our relationship with our young people by creating relationships that are simultaneously more empowering and more effective for instructors and students alike. This is a must read for anyone working in the fields of wilderness therapy and outdoor education. —Dr. Jay Roberts, Ph.D., Associate Professor of Education, Earlham College

This book is a wonderful guide, not only for parents of “troubled” or “resistant” kids, but for every parent. If Mark had given only bullet points, like so many other books do, I'd have read and forgotten them by now. Instead, through the memorable stories Mark tells, the lessons are still clear in my mind. I wish I could have read this wise book when our children were younger, but I’ll buy it for them now before they make the same mistakes with our precious grandchildren. —Ben Leichtling, Ph.D. Author of “How to stop bullies in their tracks” and “Bullies Below the Radar.”

Waltzing with Wolverines is a remarkable piece of work. This is a book of practical, nuts-and-bolts wisdom about working with youth on the edge. Anyone who works with young people will find useful ideas and inspiration in these pages. —Mark Gerzon, author of 'Leading through Conflict' (Harvard Business School Press)

If you are a parent, you need to commit the principles and techniques expressed in this book to your heart and mind so that you can remain sane during adolescence. If your child is already a teenager this book will become your and your child's best friend. Using the techniques expressed so eloquently by the author allows you not only to reconcile problems expressed by your children, your spouse, your colleagues but also to reconcile the more frustrating and problematic non-expressed problems, all in a non-confronting manner. This book should be a mainstay of communication programs. —Melissa J. Roth CHt., Ph.D.

Mark doesn’t just discuss theories and philosophies of becoming a master facilitator for “at risk” youth, he models how it works in almost any possible scenario with brilliance, patience and true genius! If you want to become a master leader with teens in any venue, then this book is your bible for how to do it with great humanness, compassion, humor and brilliance. —Kimberly Kassner, author of, You’re a Genius—And I Can Prove It! and Founder of EmpowerMind

Introduction

The Key to it All

After working just over two years as a field instructor for groups of teens in the Monarch Center wilderness therapy program, I walked into my boss’ office to tell him I’d finally decided to move on to the next phase of my career. I don’t know what I expected, but Nick’s response surprised me: “I didn’t think you’d last beyond your first expedition,” the ex Army Ranger exclaimed, shaking my hand with a firm grasp despite missing nearly all of four fingers on his right hand. Then he hugged me.

“You didn’t think I’d last beyond my first expedition?” I asked, taken aback. I admired and respected Nick not only for the way he seamlessly carried out his difficult job of hiring and overseeing field instructors (a responsibility I was glad to never have), but also for his wisdom in working and speaking directly with the kids in our program.

“When I first met you I thought the kids would eat you up,” Nick said. “You seemed so kind and innocent.”

Memories from expedition after expedition flooded through me, reminding me why so many field instructors didn’t last. There was the time Toby drank his own pee and pooped in his hands, chasing the other kids around camp with the weapon of mass disruption, then dropping his bio-terrorism in favor of threatening to stab me with his tent stakes. There was Roger, who snuck in a bottle of Advil and took enough that he started hallucinating, frantically searching through his tent for a non-existent necklace that he eventually “found” but understandably had trouble putting on. There was the expedition when Tom and Ken stole my Subaru key and managed to use it to start the Monarch pick-up truck in the middle of the night, escaping to a nearby town where they robbed a ski shop, outfitting themselves with Billabong clothing before driving the wrong way down a one-way street only to discover a police car coming the other direction. Dawn ran away one night and hitch-hiked all the way to Kentucky. When I took Jordan to get a physical he lied to the doctor, saying he wanted to kill himself, so the hospital refused to give him back to me. On a service project in New Orleans three kids ran off at night and I chased them from bar to bar in the Monarch van (complete with butterfly logo and “Family Healing” painted on the side). And on our drive to New Mexico, Adrian had a temper tantrum and shattered the front windshield of the car.

Even at the very end of my time at Monarch, I never knew what strange adventure awaited. There were the girls who cheeked their meds, crushed them up, and did lines off the office toilet seat. Another group managed to find not only marijuana as we hiked through the Loveland ski area one summer, but also a pipe to smoke it in. Nicholas refused to be a part of Monarch and started walking away down a dirt road that went for miles through the desert (I followed after him in the van, where I could listen to music). Mik pretended to strangle himself with pea cord from his tent. Percy punched a tree and sprained his hand. Abe smuggled in a condom and flashed it to one of the girls (hopefully he’s thought up better pick-up lines since). Four kids teamed up in the creative effort of growing mold on their old orange peels so they could use it to get high. And there was Ben, who went limp like a rag doll, refusing to move or speak at all, but he was considerate enough not to put up resistance when we needed to move him.

These experiences profoundly transformed my understanding of how to work with youth, teaching me vital lessons that I want to share with you, so you can be as impactful as possible with the kids in your life. Of course as I stood there in Nick’s office, I didn’t know that I’d be writing this book. At the time I simply gained a new appreciation for everything I’d learned along the way that helped me not only keep my job, but thrive in it. And of all the crucial tricks and tools that I learned, there was one important lesson that I’ll never forget, because it gave me the key to it all, unlocking my ability to flourish where Nick originally thought I would fail.

It happened when I got into a confrontation with a student while I was leading my second expedition. The confrontation wasn’t life threatening, nor was the conflict itself particularly noteworthy. But the interaction forced me to re-think my behavior and discover the confidence to easily face and out-pace much more difficult conflicts throughout the expeditions to come. What I learned—and soon confirmed through countless other experiences—became the baseline for everything I did with the kids, leading me to modify Monarch’s most fundamental principle of teen leadership to fit my new reality.

The story begins the way many confrontations begin, with something very trivial that suddenly gets blown way out of proportion. It was the beginning of our backpacking expedition, and we had made camp on the side of a hill in a clearing with scattered pine and aspen. I told the students it was time to write their daily reflection paper, which they began to do, all except Jill. She refused.

“Jill, it’s part of the assignment for being out here.”

“I don’t care.”

Uh-oh, I thought, this kid isn’t doing what I tell her to do! I have to assert control… “Alright Jill, you can have your dinner as soon as you finish.” Ha, that should do it, who wants to go hungry?

“OK, I just won’t eat.”

The little brat! That was when I got an anxious feeling in my gut. If I don’t assert control now the whole group will realize their new leader is a pushover. It’ll be mutiny! Here’s my first power-control battle, I realized. Monarch’s most fundamental principle, which they taught to all their field instructors, was, “Never get into a power-control battle, but if you do get into a power control battle, win it.” I had failed the first task of not getting in it, so I resolved to do whatever it took to win the battle.

“If you don’t do the assignment, I’ll take away one of your family overnights,” I told Jill, playing my trump card. After each expedition, any kid that had been good would earn several nights to leave the field and be with their families who had travelled to Georgetown to participate in family therapy before the next expedition. Though most of the kids were in this program because of trouble with their families, they almost invariably preferred to spend time with their families rather than stay camping in the elements. Family overnights meant access to hot showers, restaurant food, candy, music, movies, technology, and all kinds of things the kids valued highly but didn’t get out in the wilderness. Things had to be pretty bad with their families to forgo all of these benefits. During my two years at Monarch I can remember only one kid who opted to stay in the field rather than spend time with his family. To almost every student at Monarch, family overnights were valued higher than anything else.

“Fine, take away my overnight,” Jill said angrily.

Gulp. What now? “If you don’t do your assignment, I’m taking away all your family overnights,” I proclaimed, and I turned around and retreated to my tent, having exhausted my largest round of ammunition.

I felt awful. I was pretty much praying for her to finish the stupid assignment so I wouldn’t have to take away all her family overnights. I really didn’t want to do that to her. I had blown things completely out of proportion, and all because I’d felt trapped into having to assert my authority. I’d been told that if I got into a power control battle, I should win it, and as it turns out, that’s what I did. Jill ended up doing the assignment, and I let her keep her overnights, but still it felt all wrong. What was the point of threatening a kid to obey you? That isn’t therapy, it’s awful.

That got me thinking a lot during my off-shift, and when I came in for my next three-week expedition leading a new group of eight male teens, the first thing my boss said got me thinking even more. “The group’s doing great,” Nick briefed me. “The kids think Tristan is a god; they’ll do anything he says!”

Tristan was one of the male field instructors on the opposite shift. He had a similar style to most of the other male instructors at that time, a strategy of leadership that was basically that of the alpha male: You will do what I say because I’m smarter and stronger than you, and any power struggle you get into with me, you’re going to lose, period. Tristan’s strategy of leadership involved getting into power control battles with the kids, and winning them.

Nick was happy, he slept much better at night knowing that the kids were safe and under control. But there was something about this style of leadership that bothered me, and Nick had summed it up perfectly: “The kids think Tristan is a god.”

Short term, it worked great, but what about the long term goals? Did we want to teach kids to blindly obey any authority? To follow the strongest and smartest leader regardless of where they were being led? Or did we want to teach them to think for themselves and increasingly make their own choices as they stepped more and more into adulthood?

When I began my third shift with this group of eight boys, I vowed to never get into a power control battle with another kid ever again. I decided I never wanted to have another experience like what I’d had with Jill. So, for myself, I changed Monarch’s teaching on power control battles to this: “Never get in a power-control battle, but if you do get into a power control battle, get back out of it.”

I became very good at never getting into power-control battles, and just as good at noticing when I started to slip into one, so I could slip right back out. I realized that there is no power-control battle unless I agree to take a side opposite from the other person. And why would I ever want to do that? Whenever a kid refused to do what I asked, I learned to restrain from firing a new and heavier round of ammunition, widening the gulf between us. Instead I would join them and get on their side. In fact, I never left their side; that was the whole reason I was there.

If a kid objected to an assignment I gave, I’d express genuine interest in their objection, asking, “Why don’t you want to do the assignment?” Much of the time that simple question would let them know they were heard, and then they’d get on with it. If they did still have an objection, often it was pretty reasonable: “I’m too thirsty, I ran out of water on the hike and didn’t refill at our last stop.” “OK, go refill your water and then do the assignment.” Often the objection would have nothing to do with the assignment at all: “I don’t like where my tent’s set up.” Within reason, I’d do my best to accommodate their needs as long as it also met mine: that the boys and girls tents were separated far enough to meet policy, and any possible trouble-makers were separated or camped close to me.

Other times I’d join the kids a different way, yelling and stamping about in mock horror: “God, what a fucking awful assignment!” I’d say. “I can’t think of a worse way to spend my time. I’d rather die and go to hell than write another one-page check-in. You want a check in, I’ll give you a check in!” Then I’d just return to my tent. They’d comment about how crazy I was, but after my “tantrum,” they’d often find it hard to get back to their original state of defiance, and they’d just do the assignment. Other times I’d exaggerate in the other direction, with a display of over-the-top enthusiasm: “You don’t have to do this assignment,” I’d say, “You get to do this assignment! You are the chosen ones! And what you write down will be passed on from generation to generation, teaching the ways of the student Zachary for seven times seven generations! And those students will have no need for parents, simply graduating from students into field instructors, for they will have the teachings of Zachary!”

Of course sometimes they would still just refuse—to write the assignment, to hike, to do their group chores, whatever. But now when they refused, I never took on their refusal as a reflection on me, and thus never assumed a position where the group might also see it as a reflection on me. This wasn’t about me, it was all about them. If they didn’t do the assignment, I explained that was their choice, and they could work it out with their therapist. Not doing the hike was also a choice they could make, which would mean our group wouldn’t make it to our next camp. Not doing group chores was another choice they could make, which had its own consequences with the group. Often I would completely delete myself from the situation, which immediately eliminated a lot of resistance. When I truly realized that nothing was about me, suddenly everything was easy. I didn’t have to prove anything. I was here to support the kids, not coerce them.

Even with very intense confrontations, I never again experienced a need to enter into a power control battle. It may be difficult to believe, but it’s true—and that’s what much of this book is about. It’s also extremely important to realize that most confrontations never got to the point of great intensity. If I had a lot of stories of huge conflicts and confrontations to share with you, that would be a sign that the methods I used weren’t very effective. I have some stories of major conflicts—I wasn’t perfect—and you can read about how I managed them, but you’ll see that the true proof of the tools I have to offer lies in their ability to set the stage so that conflict is worked through long before things get dangerous or damaging. There’s only so much you can do when you find yourself in the path of an avalanche, but there are endless things you can do to make sure you never put yourself there in the first place.

So here I was, more than two years after I started work at Monarch, standing in my boss’s office having just heard Nick tell me that when he first hired me he didn’t think I’d last beyond my first expedition. Nick shook his head and looked me in the eyes as he said, “I couldn’t have been more wrong about you. When you were out in the field, I always slept well. After you worked a few expeditions, I knew that no matter what crazy shit went down, you’d handle it. I’m gonna miss you, man.”

“I’m gonna miss you too,” I said, deeply touched by Nicks appreciation.

But I was still taken aback. This was the first I’d heard that he initially never thought I’d survive at Monarch. Suddenly a new perspective fell together in my mind. I saw the male instructors that Nick had hired before me—the classic alpha male mountain man type. Then I saw the male leaders Nick had hired after me—softer spoken men about whom I’d initially held similar doubts as to their ability to lead a group of rowdy kids. Had I inadvertently shifted the culture of leadership at Monarch?

Of course the answer to that question really isn’t important. What’s important is that it is possible to lead both gently and firmly. It takes time and dedication to build relationships on an equal level with challenging kids, but if you care enough to do this, you will have influence that is greater than the most fearsome alpha male, and it will be the kind of influence that will continue to guide them throughout their lives, long after you’ve gone.

After implementing the specific, practical tools in this book, you may be surprised to find your group more or less leading themselves, replacing “Lord of the Flies” with a small community showing genuine respect and support for each other. The following pages are filled with story after story from my experience demonstrating exactly how to achieve this kind of success with any kids. Because if it can be done with a bunch of teens who are forced to be in a place they hate, it can be done anywhere, whether on a wilderness trip, in the classroom, or at home with your own children. Whether you are a parent, a teacher, a youth leader, or a human being wanting to connect with and support the teens in your life, may this book offer you an enjoyable roadmap on the journey.

Click here to buy the e-book and get all the stories and the 48 principles.